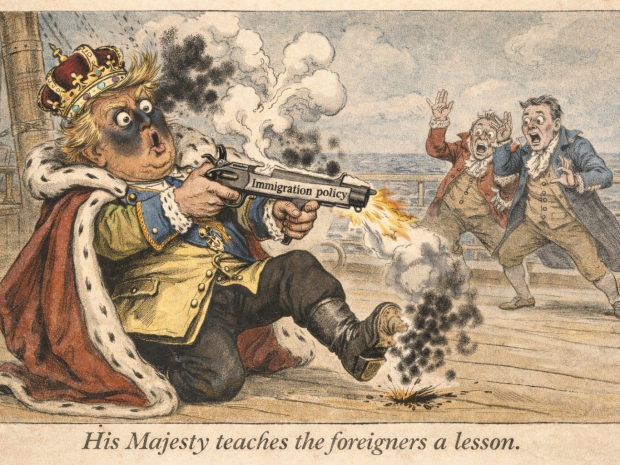

Vaughan-Nichols said that after President Donald Trump returned to office in January, European conference attendees told him they would not take jobs or attend conferences in the United States.

The mood is not exactly mysterious when the US feels like it has “Keep Out!” and “No Trespassing!” signs nailed to the arrivals hall with bizarre rules about handing over all your data to check you have not made a social media post taking the Michael out of Trump.

He said that even top tech people who flew in with proper visas and paperwork were getting turned away at the border.

Trade show organisers are seeing the same pattern, and they are not pretending it is a blip. Getting speakers and attendees from outside the States to commit to US events is getting harder, and plenty refuse to try.

Show managers are already closing US-based events and looking at replacements in Europe, Canada and Asia, where the worst part of travel is usually the coffee.

Scientific meetings are feeling it too, with organisers reporting falling attendance from abroad. PhysicsToday reports that scientists cite “visa woes and worries about being hassled, detained, or denied entry at the US border” as key reasons international researchers now give American events a hard pass.

That caution is bleeding into consumer tech as well, right when the gadget circus needs bodies in the room. Chinese tech workers invited to CES in Las Vegas, only days away, report unusually high rates of US visa denials.

Some advisers in China now warn that mentioning CES in an application can sharply increase the odds of rejection. CES organisers have acknowledged the problem and urged Washington to speed up business-travel visa approvals, and their appeals are going nowhere fast.

This is not only about conferences and speaking slots, but also about people deciding the US is not worth the hassle for work. Foreign technologists and researchers are increasingly avoiding long-term moves as visas tighten, and the political climate gets nastier.

The Trump administration’s “Restriction on Entry of Certain Nonimmigrant Workers” imposes an annual fee of $100,000 per H-1B application, which looks a lot like a hiring deterrent in the form of paperwork.

Even foreign workers already in the US are reconsidering life in a country that acts officially hostile to anyone who is not of European descent. A Specialist Staffing Group report found that 32 per cent of US-based STEM professionals are open to relocating, and that projects are already being delayed.

Major tech firms, including Amazon, Microsoft and Google, have reportedly urged overseas staff to return quickly while warning them to limit dependants’ travel. At the same time, those same firms have been laying people off, so the welcome mat is missing, and the floorboards are loose.

While the US raises barriers, rival hubs are flogging themselves as open and predictable, with Canada, Europe and parts of Asia pushing fast-track visas and remote-work-friendly policies. Engineers, founders and researchers are doing the maths and deciding the uncertainty is not worth the ticket price.

There was a time when tech talent would uproot their lives for the US because it offered collaboration, publishing, company-building and a big conference circuit. Now they run a gauntlet at the border, where even a green card or citizenship does not guarantee they will not be hassled.