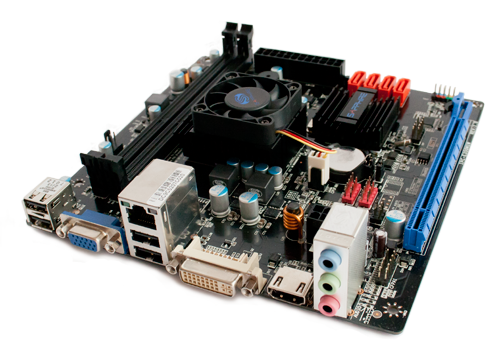

Small wonder, then, that long time ATI/AMD partner Sapphire was one of the first to embrace the new chips and offer them in micro-ITX flavour. Interestingly, the company offered Brazos boards, the Sapphire PURE White Fusion Mini we are testing today, and the PURE Fusion Mini, which offers a few additional features and relies on SO-DIMM memory rather than plain DDR3 modules. So, the White version is a simpler and cheaper design, which is by no means a bad thing. We are talking about frugal computing here, no need for bells and whistles, a decent price tag and feature set will do.

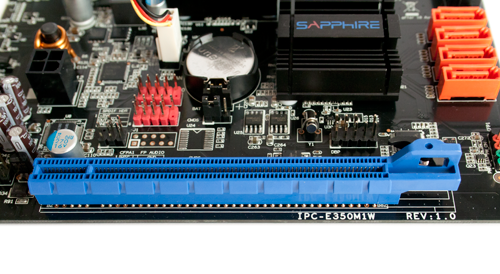

As far as the design goes, there is nothing out of the ordinary to report, it’s more or less your standard Brazos ITX board. However, a few of our staffers found it amusing that a board dubbed Pure White Fusion features a sleek black PCB, which made us think that someone at Sapphire has a healthy British sense of humour.

Although this is the cheaper of Sapphire’s two Brazos boards, and for that matter one of the cheapest ones on the market, the designers still managed to squeeze in solid-state capacitors without breaking the bank. However, the board lacks some features found on high-end Brazos products, including USB 3.0 and eSATA. Other than that, the specs are pretty much in line with the rest of the Brazos crowd: 1.6GHz E-350 APU with HD 6310 graphics, 2 DDR3 DIMM slots, 1 PCIe x16 slot (x4 in the real world), 4 external USB 2.0 ports and headers for four more, Ethernet, three audio jacks and video output is catered to by VGA, DVI and HDMI ports.

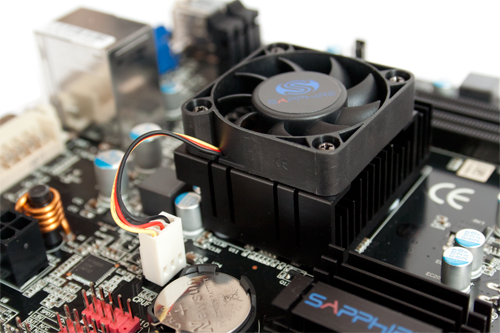

The APU is actively cooled by a tiny, but relatively quite fan, while the A50M chipset is cooled by a neat black heatsink. The layout is pretty straightforward, but it’s really not too important. Since we are talking about an integrated ITX board, consumers probably won’t be plugging too much stuff into it anyway. Speaking of which, BIOS options are rather limited, but then again few people would tinker with an ITX board and overclocking/underclocking support is uncommon on integrated ITX boards.

So, what’s missing on this entry level board? As it turns out, not much. Of course, it would be nice to see USB 3.0 and eSATA, but at this price point you just can’t find an ITX board that has them. The same applies to onboard WiFi, which would have been a nice touch but it is still reserved for pricier models.

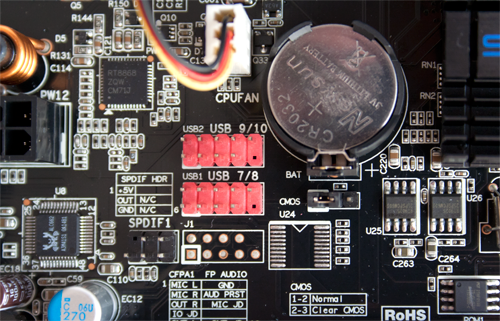

We guess a lot of people have old wireless USB adapters they can recycle anyway, but this means they will be down to three USB ports. A separate wireless keyboard and mouse combo will take up an additional two, which means there is just one left for external storage, or perhaps a TV tuner. Of course, you can use the extra USB headers for an additional four devices and it is always a good idea to check the layout of any ITX chassis you choose. Most feature two USB ports on the front, but some models sacrifice practicality for design, so the USB ports might be poorly placed or located under a flimsy plastic flap, which is hardly a good solution.

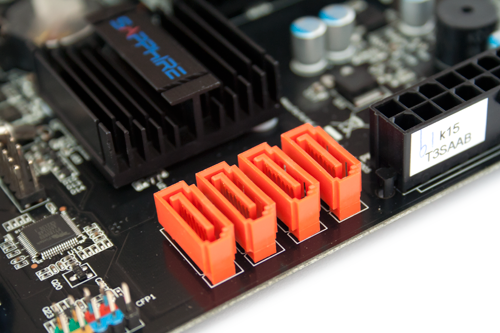

The layout is pretty straightforward and you shouldn’t have much trouble with the build. USB headers, LED and fan connectors should give you no trouble. The same applies to the four orange SATA 6Gbps ports, but you will find access to them a bit cramped in some chassis designs. Of course, this is a minor issue and few people will use more than two SATA ports anyway.

The placement of DIMM slots is unproblematic and the board supports up to 8GB of DDR3 1333 memory, which is more than enough for any HTPC.

The board also features a PCIe 2.0 x16 slot (x4 electrically, of course). We guess most users won’t use it, but it could come in handy for some future upgrades. This is where AMD has a clear advantage over Intel. Brazos supports faster DDR3 memory, and more of it. Many cheap Atom boards still cling to DDR2, which is slower and twice as expensive as DDR3. In addition, Brazos boards ship with PCIe 2.0 and SATA 6Gbps support, offering greater flexibility and upgradeability. A couple of years down the road users can squeeze some extra performance from their Brazos rigs, with cheap-low profile discrete graphics or speedy SATA 6Gbps solid state storage, which really isn’t the case with Atom boards.

Performance

In terms of performance, the E-350 is hardly a new product and there is not much point in running a bunch of comprehensive tests. It’s faster than current generation Atoms, but bear in mind that Cedar Trail should be out any day now. Even AMD launched the updated E-450 a couple of months back, but there is a catch – you can’t actually buy any.

Cedar Trail, Intel’s much touted next generation 32nm Atom was supposed to launch in Q3 and retailers have been listing Intel’s first Cedar Trail boards for weeks, yet they are nowhere to be found. To some extent the same applies to E-450 products. They are available in a handful of netbooks, but not in micro-ITX format and the vast majority of Brazos products are still based on the good old E-350. Besides, the E-450 offers only a minor performance boost, so you really won’t be missing out on anything if you go for the E-350 instead.

There is no clear or simple explanation for this, although Intel faced some driver issues with Cedar Trail graphics, but we reckon it also has something to do with the sharp decline in netbook shipments and there is a chance both AMD and Intel are affraid of being stuck with inventories of old chips, so we wouldn’t hold our breath waiting for their successors.

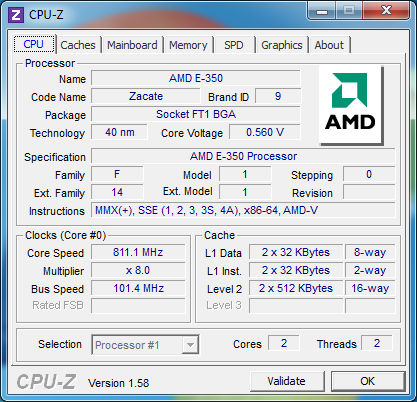

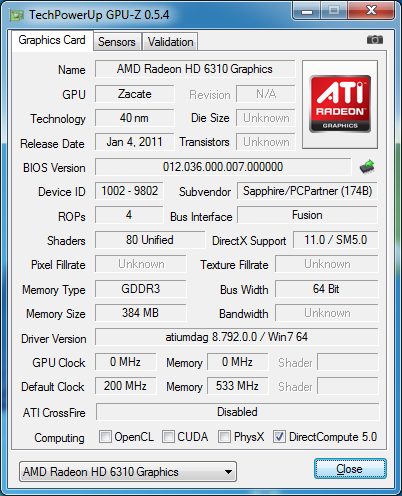

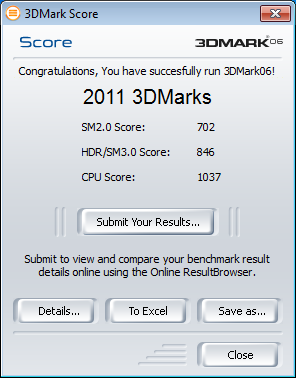

Let’s kick off with the customary CPU-Z, GPU-Z and 3dmark06 screens.

Sadly, we couldn’t get our hands on any E-450 or Cedar Trail gear, so it is really hard to say how the E-350 stacks up against these upcoming platforms. We can only compare to it to Intel’s Atom D525 with ION2 graphics and another E-350 system from Zotac.

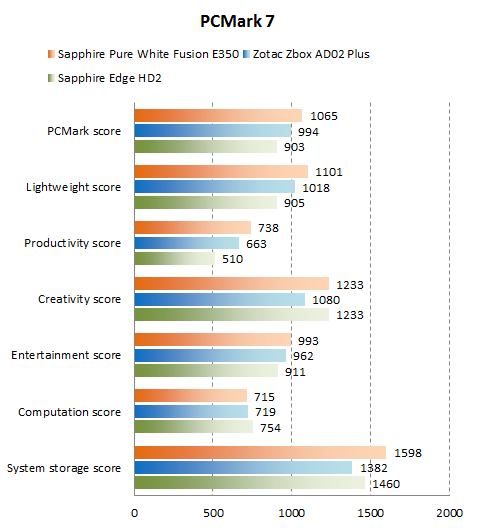

In most PCmark7 benches, the E-350 easily outpaces the Atom, apart from the creativity score, which favors the multithreded Atom.

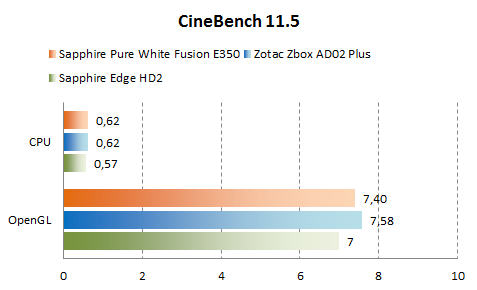

To some extent this also applies to CineBench tests, the Atom does rather well, but only on account of HT support.

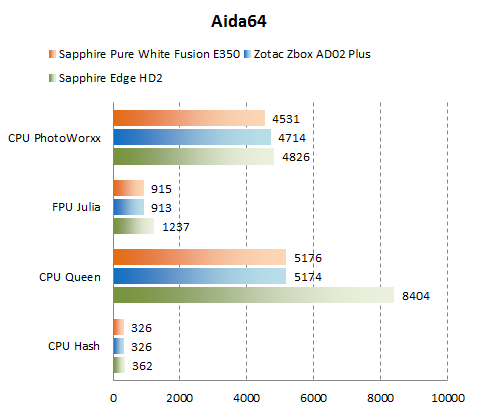

In Aida64, the Atom comes out on top on account of its superior FPU, HT and somewhat higher clock (1.86GHz vs. 1.6GHz)

The results might seem like a draw, but in real life applications Brazos will outperform any Atom system, regardless of clock, or the aid of Nvidia graphics. The E-350 simply delivers superior performance where it really counts when it comes to HTPCs. In graphics, browsing and even power consumption, it is somewhat superior to even the fastest Atom chips. Intel on the other hand has a clear advantage in heavily threaded applications and transcoding, which is really not your average HTPC workload, unless you plan to use iTunes on a daily basis.

Conclusion

We have no trouble recommending the PURE White Fusion to anyone looking for a Brazos board on a budget.

At €80 it is one of the cheapest E-350 boards on the market and only ASRock and Gigabyte offer comparable boards in terms of features, performance and pricing. For some reason US consumers will have a bit more trouble and a lot less choice if they opt for an entry-level Brazos board, as some of these boards are rather hard to come by across the pond.

So, it offers good value compared to its Brazos siblings, but what about cheap and abundant Atom boards? Well, it does not look good for Intel. The cheapest Atom D525 boards cost about €59, which sounds like a fair deal. However, they use either DDR2 or DDR3 SO-DIMM memory which negates much of the price advantage after you factor in, say 4GB of RAM. Furthermore, cheap Atom boards feature Intel GMA 3150 graphics, which should probably be banned by the UN Security Council as an affront to humanity. Basically you can forget about HDMI or DVI.

Only one scenario in which Atom D525 boards sans ION2 graphics should even be considered comes to mind – if you are looking for a silent, passively cooled office nettop that will never do anything remotely entertaining and you already have a VGA-only monitor on your desk. If this is not the case, and it probably isn’t, join the club and get a Brazos board.